Investigate the concept of phase by looking at sine waves and passive components

After introducing the SMU ADALM1000 in the December 2017 Analog Dialogue article, we wanted to continue with the sixth part of our series and take some small basic measurements. You can find the first ADALM1000 article here.

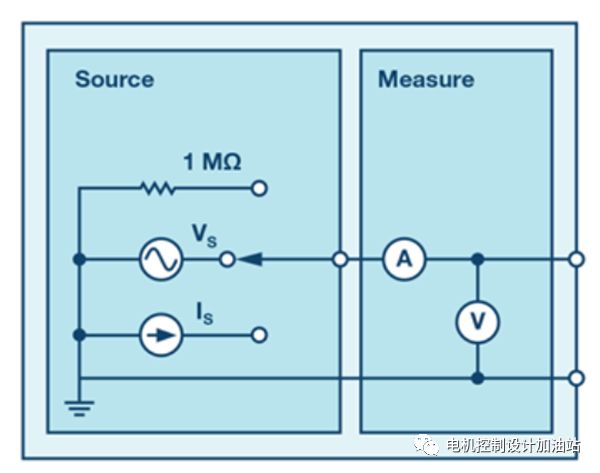

Figure 1. Schematic of the ADALM1000.

Purpose:

The purpose of this lab activity is to understand the implications of the phase relationship between signals and to understand the agreement between theory and practice.

background:

We will investigate the concept of phase by looking at sine waves and passive components, which will allow us to observe the phase shift of a real signal. First, we'll look at the sine wave and phase terms in the argument. You should be familiar with this equation:

ω sets the frequency of the sine wave as t progresses, and θ defines the time offset that defines the phase shift in the function.

The sine function produces values ​​from +1 to -1. First set t equal to a constant - say, 1. The parameter ωt is now no longer a function of time. When ω is in radians, the sin of π/4 is about 0.7071. 2π radians equals 360°, so π/4 radians corresponds to 45°. In degrees, the sine of 45° is also 0.7071.

Now let's change over time as usual. When the value of ωt varies linearly with time, it produces a sine wave function, as shown in Figure 1. The sine wave goes from 0 to 1 to -1 and back to 0 as ωt goes from 0 to 2π. is one period of the sine wave or one period T. The x-axis is the time-varying parameter/angle ωt, which varies between 0 and 2π.

In the function plotted in Figure 2, the value of θ is 0. Since sine(0) = 0, the curve starts at 0. This is a simple sine wave with no time offset, which means no phase offset. Note that if we use degrees, ωt goes from 0 to 2π or 0 to 360° to produce the sine wave shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Two Sine(t) loops.

What happens when we plot the second sine wave function in Figure 2 with ω, where the same value and θ are also 0? We have another sine wave falling on top of the first sine wave. Since θ is 0, there is no phase difference between the sine waves, and they appear the same in time.

Now change θ to π/2 radians, or 90°, for the second waveform. We see the original sine wave and the sine wave shifted to the left in time. Figure 3 shows the original sine wave (green) and the second sine wave (orange) with their time offsets. Since the offset is constant, we see that the original sine wave is shifted in time by the value θ, which in this example is 1/4 of the wave period.

Figure 3. Green: Sine(t), Orange: Sine(t + π/4).

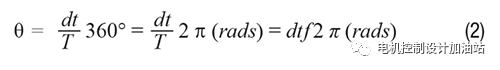

θ is the time offset or phase portion of Equation 1. The phase angle defines the time offset and vice versa. Equation 2 shows this relationship. We happened to choose a particularly common 90° offset. The phase offset between the sine and cosine waves is 90°.

When two sine waves are displayed, e.g. on an oscilloscope, the phase angle can be calculated by measuring the time between the two waveforms (negative to positive zero crossings or rising edges, which can be used as time measurement reference points). waveform). One full cycle of a sine wave is the same as 360°. Take the time ratio between the two waveforms dt and the time in one cycle of the full sine wave T and you can determine the angle between them. Equation 2 shows the exact relationship.

Mutually:

where T is the period of the sinusoid.

Naturally Occurring Time Shift in Sine Waves: Some passive components create a time shift between the voltage across them and the current through them. The voltage and current through a resistor is a simple time-independent relationship, V/I = R, where R is a real number and Ω. Therefore, the voltage and current across the resistor are always in phase.

The equation relating V to I is similar for capacitors and inductors. V/I = Z, where Z is the impedance with real and imaginary parts. We're just looking at capacitors in this exercise.

The basic rule of capacitors is that the voltage across the capacitor does not change unless there is current flowing into the capacitor. The rate of change of voltage (dv/dt) depends on the magnitude of the current. For an ideal capacitance, the current i(t) is related to the voltage by the following formula:

The impedance of a capacitor is a function of frequency. Impedance decreases with frequency, and conversely, the lower the frequency, the higher the impedance.

ω is defined as the angular velocity:

A subtle part of Equation 4 is the imaginary operator j. For example, when we look at resistors, there is no imaginary operator in the impedance equation. There is no time offset between the sinusoidal current through the resistor and the voltage across the resistor because the relationship is completely real. The only difference is the amplitude. The voltage is sinusoidal and in phase with the current sinusoid.

This is not the case with capacitors. When we look at the sinusoidal voltage waveform across the capacitor, it is shifted in time compared to the current through the capacitor. The fictitious operator j is responsible for this. As can be seen from Figure 4, when the slope of the voltage waveform (the time rate of change dv/dt) is at its highest, the current waveform is at its peak (maximum value).

The time difference can be expressed as the phase angle between the two waveforms, as defined in Equation 2.

Figure 4. Phase angle determination between voltage and current.

Note that the impedance of the capacitor is completely fictitious. Resistors have real impedance, so a circuit containing resistors and capacitors will have complex impedances.

To calculate the theoretical phase angle between voltage and current in an RC circuit:

where Z circuit is the total circuit impedance

Rearrange the equation until it looks like:

where A and B are real numbers.

Then the phase relationship of current with respect to voltage is:

Material: ADALM1000 hardware module Two 470Ω resistors One 1μF capacitor

Procedure: Use ALICE Desktop to set up a quick measurement:

Make sure the ALM1000 is plugged into the USB port and launch the ALICE Desktop application. The main screen should look like an oscilloscope display with adjustable range, position and measurement parameters. Check the bottom of the screen to make sure both CA V/Div and CB V/Div are set to 0.5. Check that CA V Pos and CB V Pos are set to 2.5. CA I mA/Div should be set to 2.0 and CA I Pos should be set to 5.0. In the AWG control window, set the frequency of CHA and CHB to 1000 Hz, 90° phase, 0 V minimum and 5 V maximum (5.000 V peak-to-peak output). Select SVMI mode and sine waveform.

In the Meas drop-down list, select PP for CA-V, CA-I, and CB-V. Set Time/Div to 0.5 ms, and under the Curves drop-down list, select CA-V, CA-I, and CB-V. On a solderless breadboard, connect the CHA output to one end of a 470Ω resistor. Connect the other end of the resistor to GND. Click the scope Start button. If the board has been properly calibrated, you should see one sine wave on top of the other, with both CHA and CHB equal to 5.00 V pp. If the calibration is not correct, you may see two sine waves in phase, with different amplitudes for CHA and CHB. Recalibrate if there is a significant voltage difference.

Measure the phase angle between two generated waveforms:

Make sure that CA V/Div and CB V/Div are both set to 0.5, and that CA V Pos and CB V Pos are set to 2.5. CA I mA/Div should be set to 2.0, CA I Pos should be set to 5.0 Set the frequency of CHA and CHB to 1000 Hz, phase to 90°, min 0 V, max 5 V (peak-to-peak output is 5.0 V). Select SVMI mode and sine waveform. In the AWG control window, change the CHB's phase θ to 135° (90+45). The CHB signal should look like (before it happens) the CHA signal. The CHB signal crosses the 2.5 V axis from above below the CHA signal. The result is a positive θ, known as a phase lead. The cross-time reference point from low to high is arbitrary. High to low intersections can also be used.

Change the CHB's phase offset to 45° (90 - 45). Now it looks like the CHB signal is lagging the CHA signal.

Set the CA's Meas display to Frequency and AB Phase. For CB display, set it to BA Delay. Set Time/Div to 0.2 ms. Press the red Stop button to pause the program. Using the left mouse button, we can add marker points on the display. Use markers to measure the time difference (dt) between the zero crossings of the CHA and CHB signals.

The measured dt and Equation 2 are used to calculate the phase offset θ(°). Note that you cannot measure the frequency of a signal that shows at least one full cycle on the screen. Typically, you need more than two cycles to get consistent results. You are generating the frequency, so you already know what it is. You don't need to take measurements in this part of the lab.

Amplitude is measured using a true rail-to-rail circuit.

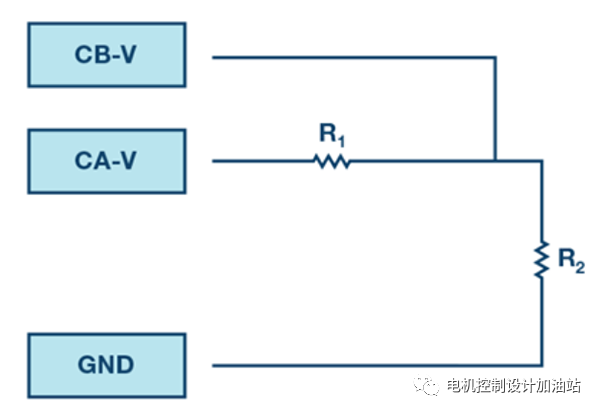

Figure 5. Rail-to-rail circuit.

Build the circuit shown in Figure 5 on a solderless breadboard using two 470Ω resistors.

Figure 6. Rail-to-rail breadboard connections.

In the AWG control window, set the frequency of the CHA to 200 Hz, the phase to 90°, the minimum value to 0 V, and the maximum value to be 5 V (peak-to-peak output is 5.0 V). Select SVMI mode and sine waveform. Select Hi-Z mode for CHB. The rest of the CHB settings are irrelevant as it is now being used as an input. Connect the CHA output to the CHB input and GND using the wires indicated by the colored test points. Set the horizontal time scale to 1.0 ms/div to display two waveform cycles. If the scope is not already running, click the scope Start button. The voltage waveform shown in CHA is the voltage across the two resistors (VR1 + VR2). The voltage waveform shown in CHB is the voltage across R2 (V R2). To display the voltage on R1, we use the math waveform display option. Under the Math drop-down menu, select the CAV-CBV equation. You should now see a third waveform of the voltage across R1 (V R1). To view the two traces, you can adjust the vertical position of the channels to separate them. Make sure to set the vertical position back to realign the signal.

Record peak-to-peak VR1, VR2 and VR1 + VR2. Can you see any difference between the zero crossings of V R1 and V R2? Can you see two distinct sine waves? maybe not. There should be no observable time offset and therefore no phase shift.

Measure the magnitude and phase of an actual RC circuit.

Replace R2 with 1µF capacitor C1.

Figure 7. RC circuit.

Figure 8. RC breadboard connections.

In the AWG control window, set the CHA frequency to 500 Hz, the phase to 90°, the minimum value to 0 V, and the maximum value to 5 V (peak-to-peak output is 5.0 V). Select SVMI mode and Sin waveform. Select Hi-Z mode for CHB. Set the horizontal time scale to 0.5 ms/div to display two waveform cycles. Since there is no DC current flowing through the capacitor, we have to handle the average (dc) value of the waveform differently.

On the right side of the main screen, there are places to enter a DC offset for Channel A and Channel B. Set the offset value as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Adjust gain/offset menu.

Now that we've removed the offset from the input, we need to change the vertical position of the waveforms to reposition them on the grid. Set CA V Pos and CB V Pos to 0.0. If the scope is not already running, click the scope Start button. Measure CA-V, CA-I, CB-V and Math (CAV-CBV) peak-to-peak. What is a math waveform?

Record V R1, V C1, I R1 and V R1 + V C1. Now let's go ahead and do something with stages. Hopefully you can see some sine waves with the time offset or phase difference displayed on the grid. Let's measure the time offset and calculate the phase difference.

Measure the time difference between VR1, IR1 and VC1 and calculate the phase offset. The phase angle θ is calculated using Equation 2 and the measured dt. Flags can be used to determine dt. Here's how.

Display at least 2 sine wave cycles. Set the horizontal time/div to 0.5 μs. Be sure to click the red Stop button before trying to place a marker on the grid. Note that markup increments display symbols that track differences.

You can use the measurement display to see the frequency. Since you set the frequency of the source, there is no measurement window that relies on this value.

If you don't see any difference in one or two sine wave cycles on the screen, assume dt is 0.

Place the first marker at the negative to positive zero crossing of the CA-V (V R1 + V C1) signal. Place the second marker at the closest positive and negative zero crossing of the math (VR1) signal. The time difference (dt) was recorded and the phase angle (θ) was calculated. Note that dt may be negative. Does this mean the phase angle is leading or lagging? To remove the marker for the next measurement, click the red Stop button.

Place the first marker at the negative to positive zero crossing of the CA-V (V R1 + V C1) signal. Place the second marker at the closest positive and negative zero-crossing of the CB-V (V C1) signal. The time difference (dt) was recorded and the phase angle (θ) was calculated. Place the first marker at the negative to positive zero crossing of the digital (VR1) signal. Place the second marker at the closest positive and negative zero-crossing of the CB-V (V C1) signal. The time difference (dt) was recorded and the phase angle (θ) was calculated. Is there any measurable time difference (phase shift) between the math (VR1) signal and the displayed CA-I current waveform? Since this is a series circuit, the current supplied by AWG channel A is equal to that of R1 and C1.

appendix:

Figure 10. Step 5 with Time/Div set to 0.5 ms.

Note: As with all ALM labs, we use the following terms when referring to connecting and configuring hardware to the ALM1000 connector. Green shaded rectangles indicate connections to the ADALM1000 analog I/O connectors. The analog I/O channel pins are called CA and CB. When configured to force voltage/measure current, add -V (as in CA-V) or when configured to force current/measure voltage, add -I (as in CA-1). Add -H (as in CA-H) when the channel is configured in high impedance mode to measure voltage only.

Oscilloscope traces are similarly represented by channel and voltage/current, such as CA-V and CB-V for voltage waveforms, and CA-I and CB-I for current waveforms.

We use the ALICE Rev 1.1 software here for these examples. File: alice-desktop-1.1-setup.zip. Please download here.

ALICE Desktop software provides the following features:

2-channel oscilloscope for time domain display and analysis of voltage and current waveforms. 2-channel arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) control. The X and Y displays are used to plot the captured voltage and current versus voltage and current data, as well as a voltage waveform histogram. 2-channel spectrum analyzer for frequency domain display and voltage waveform analysis. Bode plotter and network analyzer with built-in sweep generator. Impedance analyzers for analyzing complex RLC networks, as well as impedance analyzers for use as RLC meters and vector voltmeters. A DC ohmmeter measures an unknown resistance relative to a known external resistance or a known internal 50Ω. Board self-calibration using the AD584 precision 2.5 V reference from the ADALP2000 Analog Parts Kit. ALICE M1K Voltmeter. ALICE M1K meter source. ALICE M1K Desktop Tools. See here for more information.

Note: You need to connect the ADALM1000 to the PC to use the software.

Figure 11. ALICE Desktop 1.1 menu.

author

Doug Mercer

Doug Mercer received his bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in 1977. Since joining Analog Devices in 1977, he has contributed directly or indirectly to more than 30 data converter products and holds 13 patents. He was named an ADI Fellow in 1995. In 2009, he transitioned from a full-time job and continued at ADI Consulting as an Emeritus of Active Learning Program. In 2016, he was appointed engineer-in-residence in RPI's ECSE division.

Antoniu Miclaus

Antoniu Miclaus [antoniu.] is a systems applications engineer at Analog Devices, where he is responsible for ADI academic programs, and embedded software from Circuits for Lab® and QA process management. He started at Analog Devices in February 2017 in Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

He is currently a Master of Science. He is a student of the Master Program in Software Engineering at Babes-Bolyai University and he has a B.Eng. in the field of electronics and telecommunications at the Technical University of Cluj-Napoca.

Absolute rotary Encoder measure actual position by generating unique digital codes or bits (instead of pulses) that represent the encoder`s actual position. Single turn absolute encoders output codes that are repeated every full revolution and do not output data to indicate how many revolutions have been made. Multi-turn absolute encoders output a unique code for each shaft position through every rotation, up to 4096 revolutions. Unlike incremental encoders, absolute encoders will retain correct position even if power fails without homing at startup.

Absolute Encoder,Through Hollow Encoder,Absolute Encoder 13 Bit,14 Bit Optical Rotary Encoder

Jilin Lander Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd , https://www.landerintelligent.com